by Tenzin Choedon

There were so many stages in my life when Losar meant different things to me.

A traditional Losar shrine offering items to invoke auspiciousness and abundance for the New Year

Losar when growing up reminds me of fun and excitement. All I cared about were the new clothes, brand new shoes, money under my pillow that I always believed the Losar Fairy (my parents made sure to put the money in an envelope) had placed and of course, the fire crackers on the 29th day of the last month before Losar. The altar looked beautiful with all the Derka and offerings, but those were amongst the least of my interest although asking Konchok (god) for permission to steal some chocolates and candies, nuts and dried cheese from the altar is another thing.

Losar then began to challenge me as a grown up. I started feeling embarrassed wearing new clothes and wasn’t too excited about getting extra pocket money. Losar was about going to school and giving exams. Losar was about taking more responsibilities, it was about learning how to arrange the altar and the offerings, preparation for Guthuk, sweet rice and my favourite – butter tea.

Eating Guthuk is an important Tibetan tradition that signifies the safe passage into the New Year.

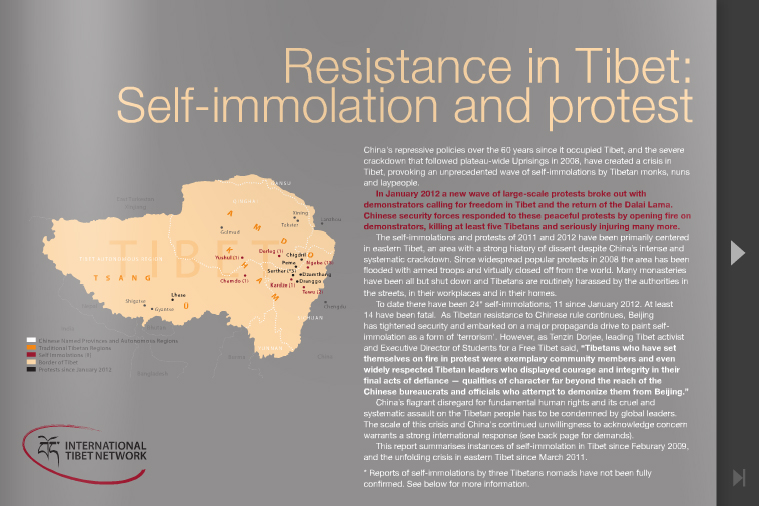

There after, Losar became a tool. A tool to get peoples’ attention to our cause. A tool for Tibetans inside to defy the Chinese authority. A tool for Tibetans living around the world to be ourselves and celebrate our existence.

Losar could be like any other new year, but to me, although the meaning of Losar varied each time, these different stages helped me grow into my identity.

The Chinese authority may try and manipulate our Losar, but they can’t take away the Spirit of Losar – the spirit of being Tibetan.